In part 1 (read here ) we defined the trunk, explored the anatomy of the trunk, and used this to help lay out the parameters for optimising our trunk training for the youth athlete.

Today’s post will dive into more detail on low load stability trunk training.

Following this article you should:

-

Understand how to determine whether your athlete may benefit from low load stability

-

Feel confident with means of assessing low load stability

-

Understand why functional and non-functional low load stability exercises can benefit an athlete

Start With Why: Low Load Stability

Let’s kick start things with a definition… Low load stability, or local muscular endurance, can provide a platform for greater developments in trunk strength and power. These exercises are intended to develop the ability to maintain a neutral spine while enduring forces from movement through a specific plane of motion (Spencer et al 2016).

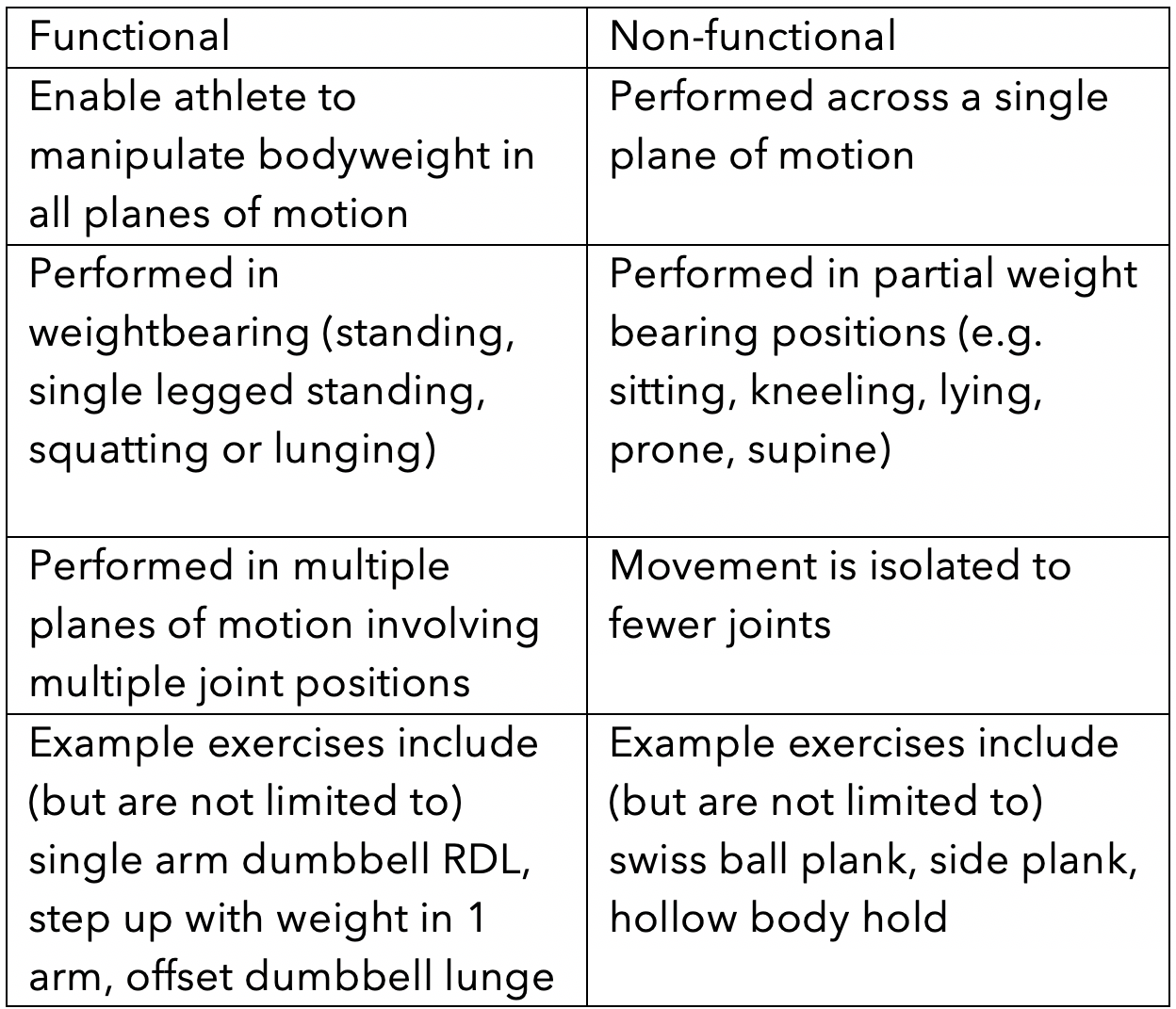

Low load stability exercises can be non-functional to functional. The word ‘functional’ has become bastardised beyond belief in the realm of strength and conditioning so for clarity sake descriptions are provided in the table below.

For simplicity sake: neither is superior… It depends on the context.

#block-6f8048fa83d520202e2d {

}

(Spencer et al 2016)

The focus here is on timing, coordination and effective spinal control during all movements. Unlike trunk strength exercises, which may involve greater muscular effort, excessive tension in low load stability exercises is unproductive and represents an energy leak.

If you’re recruiting every possible muscle of your trunk to simply to tie your shoelaces you will burn out pretty quickly.

So now we know what we are aiming for with our low load stability exercises how do we determine whether or not our athlete might need them?

Some Questions To Ask…

-

Does the athlete possess the body awareness to hold a neutral spine? If they don\’t… I would forget everything else until they can. Without this ability adding load or speed to an exercise will only result in increased injury risk.

-

Does the athlete play a sport that lasts longer than 60 seconds? If so… longer duration assessments may be considered appropriate as a reasonable test of slow twitch fibres (type I).

On a side note… Even if an athlete is involved in a sport that is over in seconds (e.g. a sprinter, shot putter, weightlifter etc), if they crumble like a dunked rich tea biscuit after a trunk assessment of more than a few seconds this glaring weakness may manifest itself in performance or increase injury risk

Low load stability forms the platform for trunk strength and endurance (think about it – f your body cannot respond to low load challenges of stability, such as changes in posture, then how do you expect to be able to handle the high loads and forces associated with sport or the weights room?)

Low Load Stability Assessments

Low load stability assessments should look to evaluate posture, stability, movement quality, endurance and dissociation (i.e. the ability to create motion with certain parts of the body whilst resisting movement in other parts of the body).

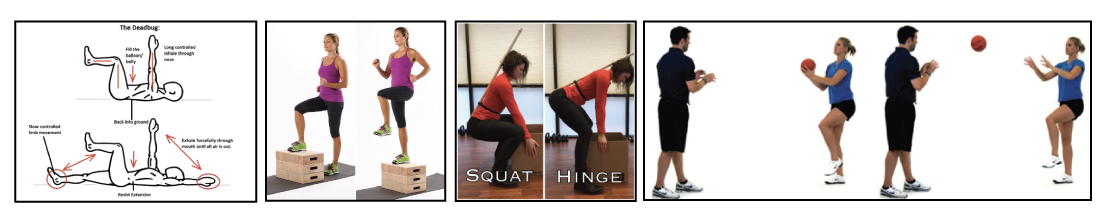

The below pictures represent low load stability assessments in all 3 planes of movement:

-

Sagittal plane – Can the athlete maintain a neutral spine whilst moving their hips up and down (squat pattern), forward and back (hip hinge pattern)?

-

Frontal plane – Can the athlete keep the knees in line with their toes during single leg stepping (step ups)?

-

Transverse plane – Can the athlete maintain balance over their base of support whilst throwing and catching a ball stood on one leg? (single leg throw and catch)

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1565356836075_24401 {

}

Typically, the trunk acts to stabilise the spine in the presence of movement, since the kinaesthetic feedback of the lower back against the ground allows the athlete to ‘self-coach’, the deadbug also makes for a great assessment tool in terms of teaching youth athletes to maintain a neutral spine.

In my personal experience, it also works wonders for creating buy in from athletes. When they can’t perform what they deem to be a relatively simple task (simple does not necessarily mean easy) all of a sudden they want to know why they can’t keep their back flat (typically it’s a hip mobility or core stability issue) and what they can do to solve it.

It is also worth noting that low load stability and high load stability (keep an eye out for part 3!) trunk exercises are more like separate entities than a continuum. A powerlifter might be able to demonstrate impressive levels of high load stability by not folding under heavy loads… But might not have the requisite low load stability to maintain an effective posture throughout the time course of a triathlon.

As youth athletes encounter growth spurts they may find that the previously owned stability they once had has lessened somewhat.

I’ve coached a female youth athlete who could hip thrust twice her body weight no problem… But struggled with the precision and control required for low level stability exercises, which her physio attributed to back issues she was struggling with.

It’s no good having all the horsepower (high load stability) without having the timing and control to coordinate finer movements (low load stability).

Although relating trunk work to the demands of a sport can be useful, the reality is youth athletes need both the ability to respond to small changes in posture (aka body awareness) as well as the ability to create appropriate tension when the task demands it.

Conclusion

-

Low load trunk stability exercises can form the basis for strength and power development (although just because you demonstrate a high level of ability in one, does not guarantee it for the other).

-

Low load trunk exercises should focus on precision, timing and control, rather than excessive muscular effort.

-

Just because a trunk exercise is non-functional, does not mean it doesn’t transfer, a combination of functional, and non-functional low load stability exercises should be incorporated into an athlete’s program.

Written by Todd Davidson

References

Spencer, S., Wolf, A., & Rushton, A. (2016). Spinal-exercise prescription in sport: classifying physical training and rehabilitation by intention and outcome. Journal of athletic training, 51(8), 613-628.

About the author

Todd Davidson is a UKSCA accredited Strength and Conditioning Coach currently working at Downe House school, in charge of the scholarship athletes\’ strength and conditioning program whilst introducing athletic development into the P.E curriculum.Todd\’s current interest on youth athletes was sparked by gaining experience with University, Paralympic and Olympic athletes as part of his internship roles with Duham University, Middlesex County Cricket Club and the English Institute for Sport, with GB Boxing and Paralympic Table Tennis, and speaking to other practitioners as to how this journey can be scaled more effectively to reduce injury risk, enhance performance and improve athletic development in youth athletes.

Todd can be found via:

Twitter: @todddavidson93

Facebook: search Todd Davidson P2P coaching

Instagram: @ToddDavidsonP2Pcoaching

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1565356836075_38932 {

}