Peak height velocity (PHV) describes the most accelerated growth spurt a child experiences.

In this blog you will learn:

-

The implications of PHV on injury risk, coordination and your child\’s athletic development

-

How your child\’s workload should be adapted when they go through their most accelerated growth spurt

-

Practical take-homes for managing your child’s athletic development during their peak height velocity.

You might be thinking… All children will grow, why bother reading a blog written on it?

Firstly, during peak height velocity you are effectively asking a child to coordinate a larger, longer, heavier frame. Unsurprisingly perhaps, injury risk has shown to spike dramatically around the time of this most accelerated growth spurt (Rumpf & Cronin 2002; van der Sluis 2014).

Secondly, coordination of skilled movement, be it a squat in the gym or controlling a football, can sometimes be thrown out the window during PHV, leading some researchers to term this period of time \’adolescent awkwardness\’ (Lloyd et al 2014).

Whilst not all kids experience adolescent awkwardness, all kids will experience similar trends; with arm and leg length increasing first (Lloyd et al 2014), and peak weight velocity (i.e. the most accelerated increase in weight) catching up ~18 months later.

#block-603f285b71da8144d015 {

}

During peak height velocity, kids (especially boys) develop hormonal profiles that support increased muscle mass, and as a result, even in the absence of training, will get stronger, faster and jump higher (Lloyd et al 2014).

Excellent…you might think…

..but without subsequent improvements in movement technique…you are now have an athlete who has now more gears and a bigger engine, but still cannot effectively steer the car.

During peak height velocity, kids are now in charge of a heavier, longer body and may have poorer movement technique…even by doing the same training load you will be placing more stress on a youth athlete who is going through their most accelerated period of growth.

The take our driving analogy further, which of these transitions do you think would be smoother:

-

Your child learning to efficiently drive a smaller, less powerful vehicle before eventually having to transition into controlling a larger, more powerful vehicle

-

Your child going from zero driving experience to starting to learn to drive with a larger, more powerful vehicle, whilst on the motorway at 70mph

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1574097188928_6834 {

}

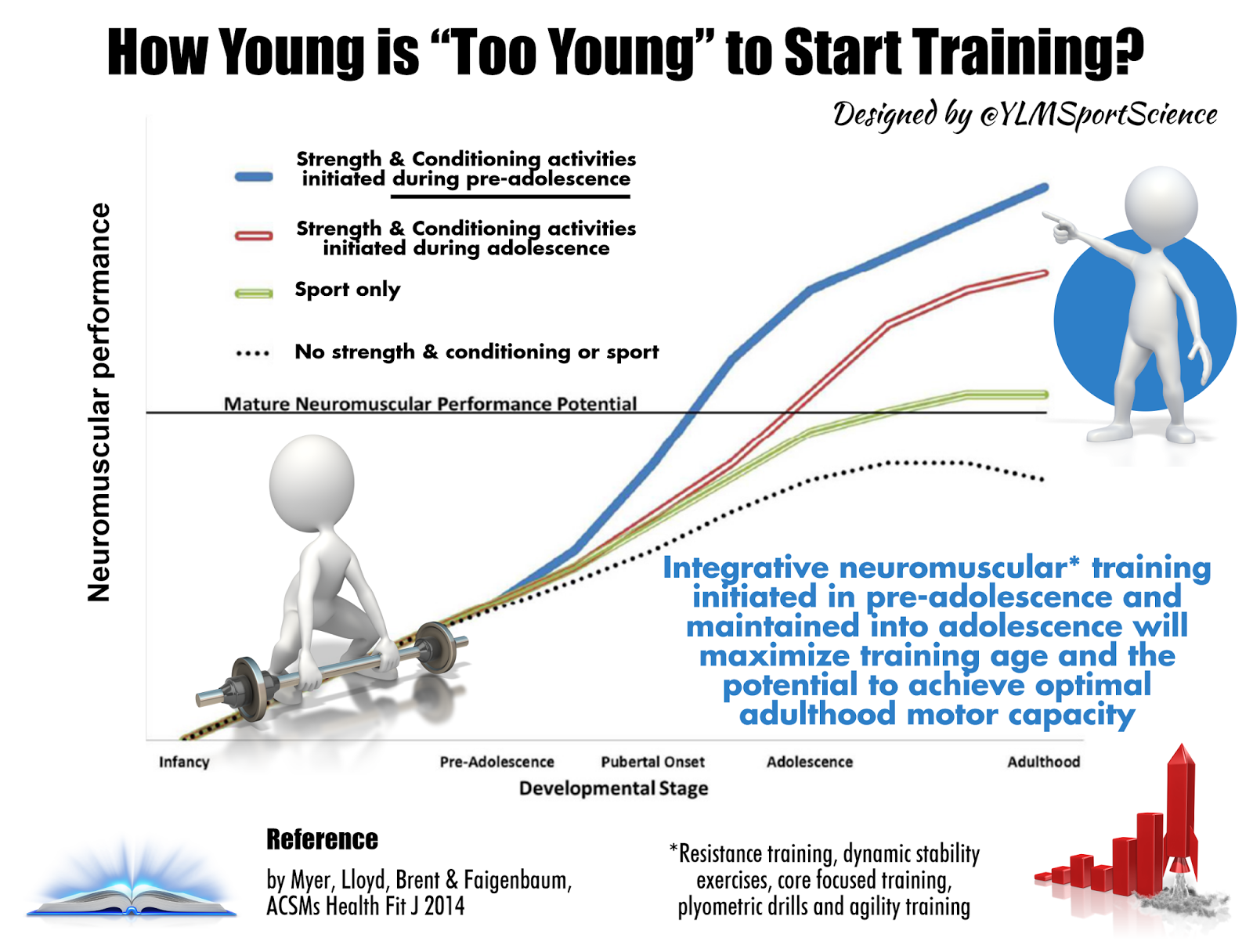

If your child has not been taught effective movement techniques, such as how to jump and land, before puberty (i.e. pre-peak height velocity), when they encounter their most accelerated period of growth, you are effectively starting their driving lessons at 70mph on the motorway and hoping they don’t crash and burn.

So, what approach does CHP take to counter the issues that arise with youth athletes and peak height velocity?

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1574097188928_19900 {

}

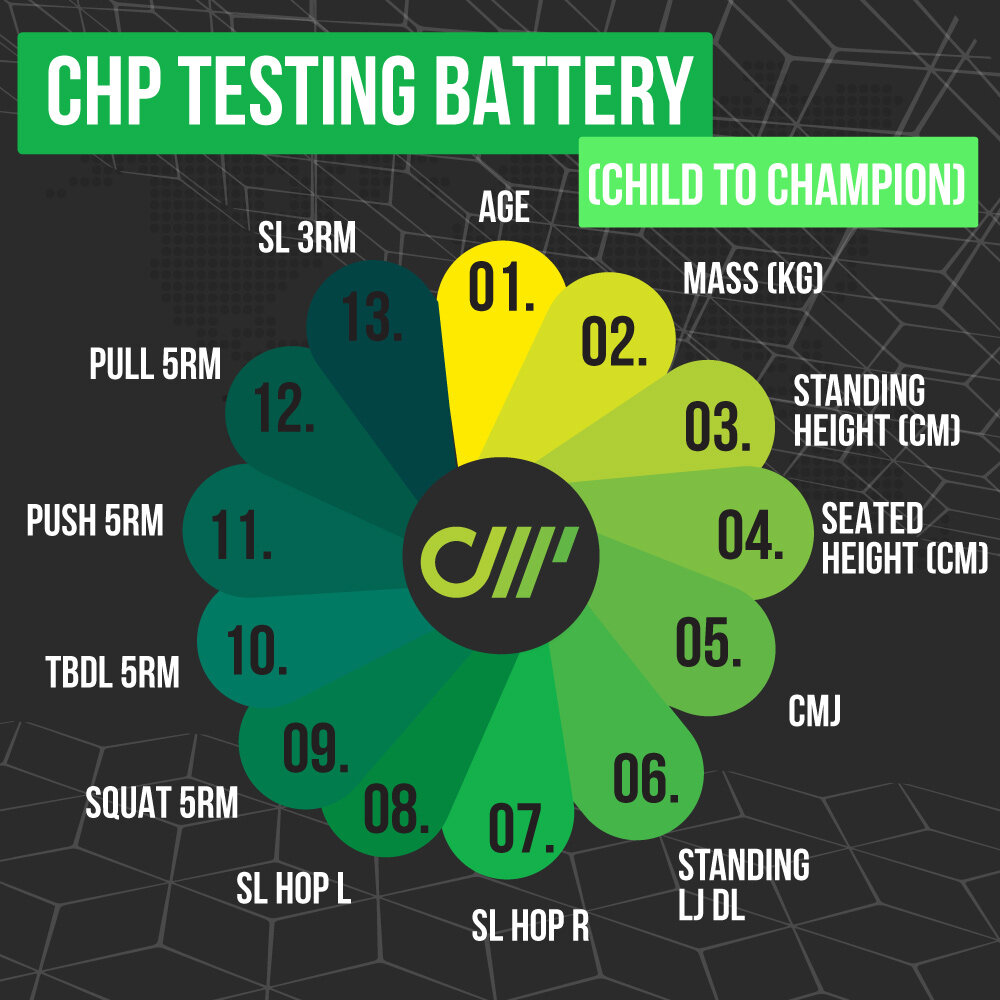

CHP assess rather than guess; measuring peak height velocity every 3 months, as well as gaining key metrics of strength, power and movement technique.

This allows for individualised workloads which help minimise injury risk.

Now compare this to what might happen where a coach has no prior knowledge or does not have a means of assessing peak height velocity…

…it’s pre-season so the coach innocently decides it\’s time to up the volume of work being done. Your child is going through their most accelerated period of growth is now someone who is longer, heavier (and without any additional increases in power or strength…certainly slower), their centre of mass (subsequently/possibly coordination) has changed. Inevitably, your child’s performance will be worse…which the coach interprets as a loss of fitness compared to previous years. As a result, the coach insists your child must now train even harder to regain the form they displayed last year.

Without an understanding or assessment of peak height velocity (or peak weight velocity) youth athletes can find themselves easily frustrated by performance loss, whether it be a result of simply being heavier, ‘adolescent awkwardness’, or as a result of being sidelined due to inadvertent increases in their workload (Rumpf & Cronin 2002; van der Sluis 2014)

So how do you mitigate the injury risks associated with your child when the inevitable growth spurt occurs?

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1574097188928_35813 {

}

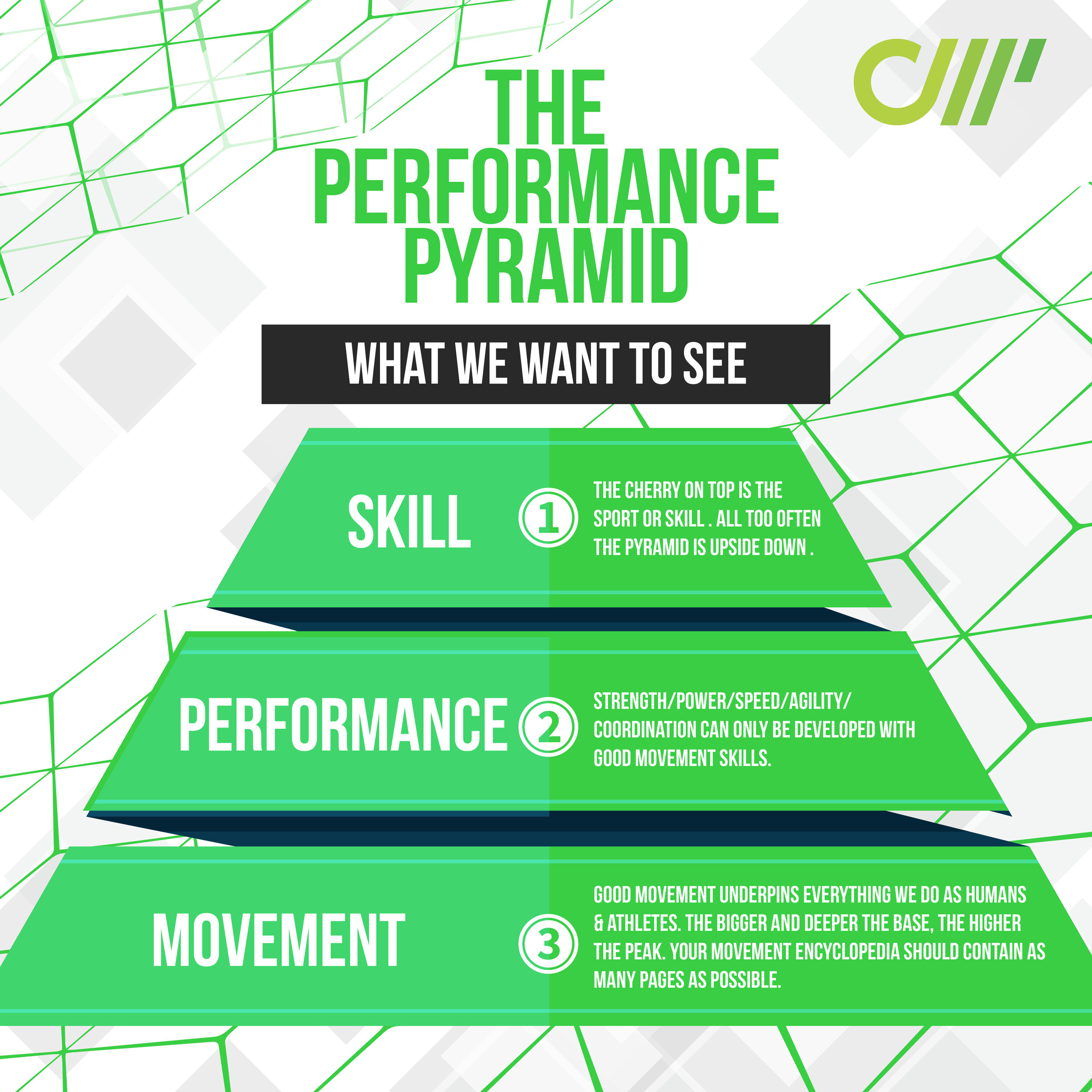

Firstly, develop a foundation of quality movement before your child goes through their growth spurt.

Re-learning movement patterns you have previously developed with a smaller, lighter and better-coordinated body is much easier than trying to learn whilst during the midst of a growth spurt.

Secondly, once your child has a foundation of quality movement in place, developing strength will help maintain power to weight ratio as your child grows.

Without appropriate increases in strength, both power to weight ratio and VO2 max (the body’s ability to utilise oxygen per kilo of bodyweight) tend to decline when a child experiences their peak height velocity.

Not only can strength training help maintain power to weight ratio, a key metric to success in both explosive and endurance sports, it can also reduce the likelihood of overuse injuries (Malone et al 2018).

Although adolescent awkwardness typically affects around 25% of pubertal athletes, it can be extremely frustrating for your child (Lloyd et al 2014).

Any child who loves their sport will have to be handled carefully during their peak height velocity both in relation to an appropriate decrease in their physical workload and most importantly by having someone explain why they may be experiencing a loss of form, and that this loss of form is not a permanent or true reflection of their ability.

Finally, and most importantly, if your child is experiencing a loss of coordination during their most accelerated growth spurt, reduce their physical workload and prioritise movement technique until they have come through their most accelerated growth spurt.

Key Take Homes:

-

Peak height velocity is the most accelerated period of a child’s growth spurt and leads to an increased injury risk

-

This injury risk can be mitigated in the long term by prioritising the development of movement technique and strength in a child’s pre-pubertal years

-

The injury risk associated with peak height velocity can be mitigating further by reducing physical workload and prioritising movement technique until the child’s finishes their most accelerated period of growth

References/Resources

van der Sluis, A., Elferink-Gemser, M. T., Coelho-e-Silva, M. J., Nijboer, J. A., Brink, M. S., & Visscher, C. (2014). Sport injuries aligned to peak height velocity in talented pubertal soccer players. International journal of sports medicine, 35(04), 351-355.

Rumpf, M. C., & Cronin, J. (2012). Injury incidence, body site, and severity in soccer players aged 6–18 years: implications for injury prevention. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 34(1), 20-31.

Lloyd, R. S., Oliver, J. L., Faigenbaum, A. D., Myer, G. D., & Croix, M. B. D. S. (2014). Chronological age vs. biological maturation: implications for exercise programming in youth. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 28(5), 1454-1464.

Malone, S., Hughes, B., Doran, D. A., Collins, K., & Gabbett, T. J. (2019). Can the workload–injury relationship be moderated by improved strength, speed and repeated-sprint qualities?. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 22(1), 29-34.

Strength and Conditioning for Young Athletes by Rhodri Llyod

About The Author

Todd Davidson is a UKSCA accredited Strength and Conditioning Coach currently undertaking a PGCE through St Mary’s University, with the longer term aim of introducing athletic development into the national P.E curriculum. Todd\’s current interest on youth athletes was sparked by gaining experience with University, Paralympic and Olympic athletes as part of his internship roles with Durham University, Middlesex County Cricket Club and the English Institute for Sport, with GB Boxing and Paralympic Table Tennis, and speaking to other practitioners as to how this journey can be scaled more effectively to reduce injury risk, enhance performance and improve athletic development in youth athletes.

Todd can be found via:

Twitter: @todddavidson93

Facebook: search Todd Davidson P2P coaching

Instagram: @ToddDavidsonP2Pcoaching

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1574097188928_46237 {

}